During the war, Vietnam defended itself using guerilla warfare, relying on stealth and sabotage to fight a superior military power. To support this, the Vietcong had a vast network of tunnels that lay beneath much of the country. We took a day trip out of Ho Chi Minh city to see a part of the system that has been preserved.

To get to Ben Duoc, the site that hosted the tunnels, we had to get a bus from Ho Chi Minh City early in the morning. Thankfully, the public buses run past the site, so we were able to just hop on and get off near the entrance. The bus driver helped us, making sure we left at the right stop.

Ben Duoc is more than just the tunnels. It’s a whole tourist destination and museum, with other activities you can try. One of the available activities was a shooting range, and I was very tempted. I haven’t fired a rifle since I was a teenager, and I’ve been itching to try it again lately. A strange feeling to have while at what is essentially a war memorial.

After entering the site we were greeted by war memorials, honouring those that sacrificed their lives to liberate the country. Near the entrance is a temple, a place where people can pay their respects.

There are many displays of weapons in Ben Duoc, giving an impression of the amount of munitions used in the war. Many spent bomb cases and shells, howitzers, and disabled rifles bring you into the world of Vietnam at war, when guns were everywhere.

Scattered about the site are several destroyed and damaged vehicles recovered during and after the war. Old tanks, jeeps, helicopters, and even bomber planes are on display. Most, if not all, were American, since the Vietnamese relied heavily on guerilla tactics. The invaders had an air force, the Vietcong had their tunnels.

When we got to the tunnels we found that it was a guided tour meaning we had to book a time slot. It wasn’t busy, so there were plenty of options. We picked the next one and were taken to the waiting area, past a diorama showing what resistance fighters looked like and the kind of equipment they wore.

After a few more people showed up our tour guide came to greet us and took us to watch the introductory film. The movie gave a brief overview of the tunnels, how they played a part in the war, and how they were used to help plan the Tet Offensive. Now that we had context, it was time to explore the actual tunnels.

We were taken to the parts of the tunnels that were opened, as our guide demonstrated how well camouflaged and hidden they were. Small holes poking out of fake rocks, slits at the edge of overgrown mounds where a gun could poke out. They were used both for spying on American troops, and for taking pot shots at them.

Our guide was both informative and entertaining. He encouraged us to enter the tunnels and engage with what he was teaching us. Later he would tell us that only Vietnamese could work here, a way of keeping the history authentic.

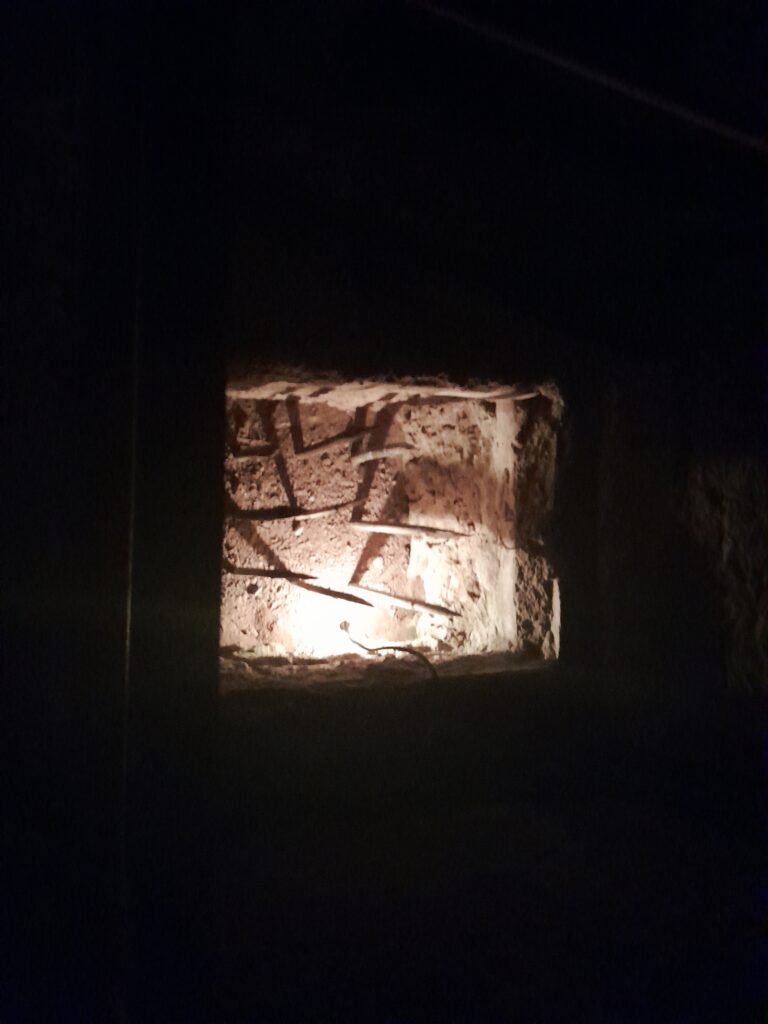

Next we were shown how to get into the tunnels through a hidden entrance. We were allowed to crawl in and actually see and feel what it was like down there. The tunnels here have been widened and have lights installed, so they’re a little easier to navigate than they were during the war.

Still, you get the sense of how cramped everything is. You still have to duck and weave, and your shoulders inevitably brush against the walls. Most tunnels are wide enough only for one person and they connect to chambers with low ceilings. The most spacious chambers were often positioned as lookout or sniper points. The places where soldiers would spend the most time.

The air is musty and the smell of earth lingers in these tunnels. Our tour guide showed us the ventilation shafts they used to stop the air going stale, but even these had to be hidden. Even with this ventilation, soldiers would still have to come up for fresh air from time to time, a dangerous prospect if enemy troops were in the area.

The tunnels we went into were just below the surface, but they could actually go three levels deep or more. The American invaders relied heavily on bombing Vietnam, but being this deep, they would be hard to target and harder to destroy.

Next on our guided tour we were shown the traps that the Vietcong would set up. They would have traps on the surface and within the tunnels themselves. These traps weren’t designed to kill; they were designed to maim.

A dead soldier takes out one enemy. A mutilated soldier, screaming in pain, begging for help as he bleeds out takes out many more. Other soldiers will rush to help him, or lose morale after seeing something horrific. A trap that maims, rather than killing outright, will take out many more soldiers.

We got to explore a few more tunnels, many with scenes set up of life in the tunnels. Troops carrying a wounded comrade on a stretcher. An underground dining hall. A makeshift surgery where a doctor works on a patient.

One tunnel we got to explore took us down to the second underground level and to another exit several meters away. It was dark and foreboding, feeling a lot more like must have during the war. They’ve blocked off entrances to the wider network, of course, so there was only one path and no chance of us getting lost. Yet somehow, as we crawled and clambered up makeshift stairs, it still felt like we were stuck in a maze for a short while.

At the end of the tour we got to enjoy some local Vietnamese food while we talked about our experience. I said that I had “fun.” Which felt weird when I said it. While I did enjoy the experience, and learned something new, I couldn’t help but think about how violent and dark everything about this place was.

People hiding in tunnels from an overwhelming enemy, forced to resort to horrific acts of violence to defend themselves. Barely ever seeing sunlight, living in the dark and the damp, always hiding, both in fear and in defiance.

And on the other side, the teenagers sent from America. They were told they were there to liberate Vietnam. Only to find an opposition that was willing to butcher them to defend their homes. Stuck in a violent situation, unable to get out. And when they did return home, they were spat upon by the growing number of people opposing the war.

But fifty years later, on the day we visited the remnants of these tunnels, we had fun. Is it strange, or healing, that a place of so much pain can now be a place of curiosity and even enjoyment?