After a full day visiting temples, we decided to change things up with a Museum Day, venturing out to the outskirts of Vientiane to dig deeper into Laos’ history. We wouldn’t just learn the general history, but the history they choose to tell.

Two museums sit side by side on Kaysone Phomvihane Avenue, a short ride from the city center. Conveniently close to each other, they make for a good day trip if you want to understand more about the country’s past and present.

Kaysone Phomvihane Museum

This museum is dedicated to the life and legacy of Kaysone Phomvihane, the founding leader of the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party and a key figure in the country’s liberation from colonial rule. He’s revered here as the father of modern Laos, and this museum is a monument to that reverence.

The building itself is one of the most imposing structures I’ve seen in the country. A broad plaza holds vast walkways, military statues, and a towering statue of Phomvihane that watches over visitors as they approach the grand, white façade. Gold-trimmed carvings and a bold red roof complete the sense of ceremony. You feel small here and it’s no accident. This space is designed to leave an impression.

Inside, things were quiet. The woman at the front desk welcomed us warmly, happy to have foreign visitors. After paying a small entrance fee, we were able to explore an extensive retelling of Phomvihane’s life. His childhood, political rise, military leadership, and eventual role in shaping post-independence Laos.

While the museum is certainly celebratory in tone, it’s still educational. It gives insight into how modern Laos views its past and frames its heroes. Unfortunately, photography is not allowed inside, so the experience must be carried out with memory alone.

Lao National Museum

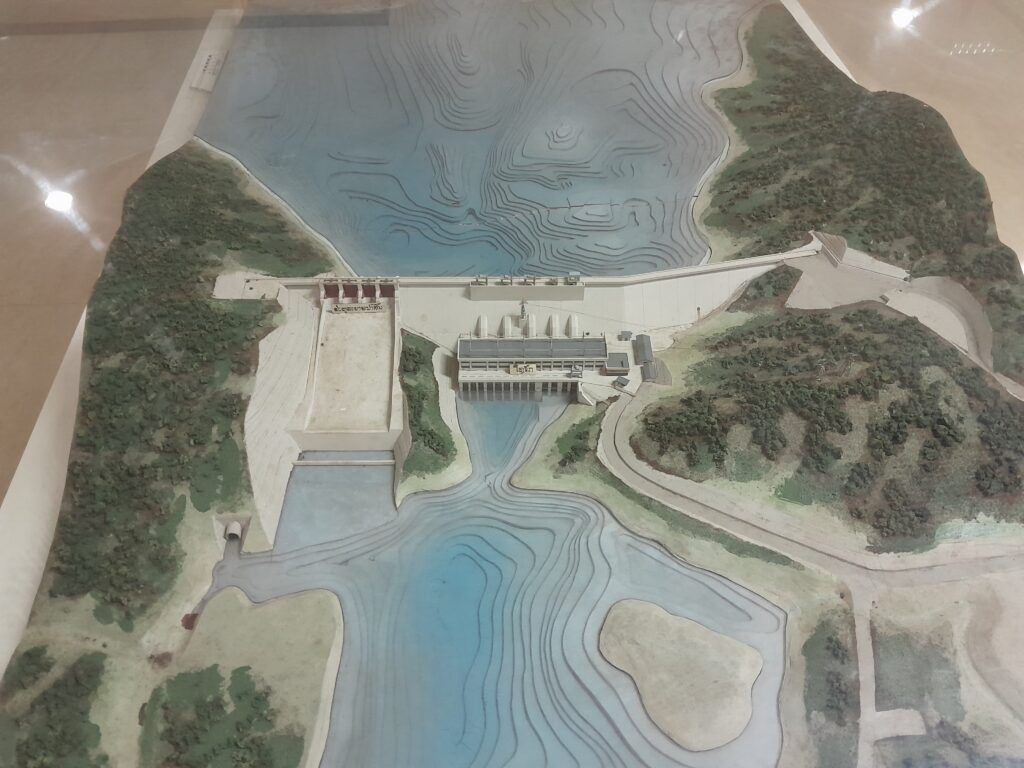

Next door is the Lao National Museum, which broadens the focus from one man to the country as a whole. It spans millions of years, beginning with prehistoric fossils, through the wars and struggles of the 20th century, and ending with modern history.

The building isn’t as grand as its neighbour, but it still has an air of importance, with traditional Laos architectural flourishes. It feels more like a traditional museum: still solemn, but less overwhelming.

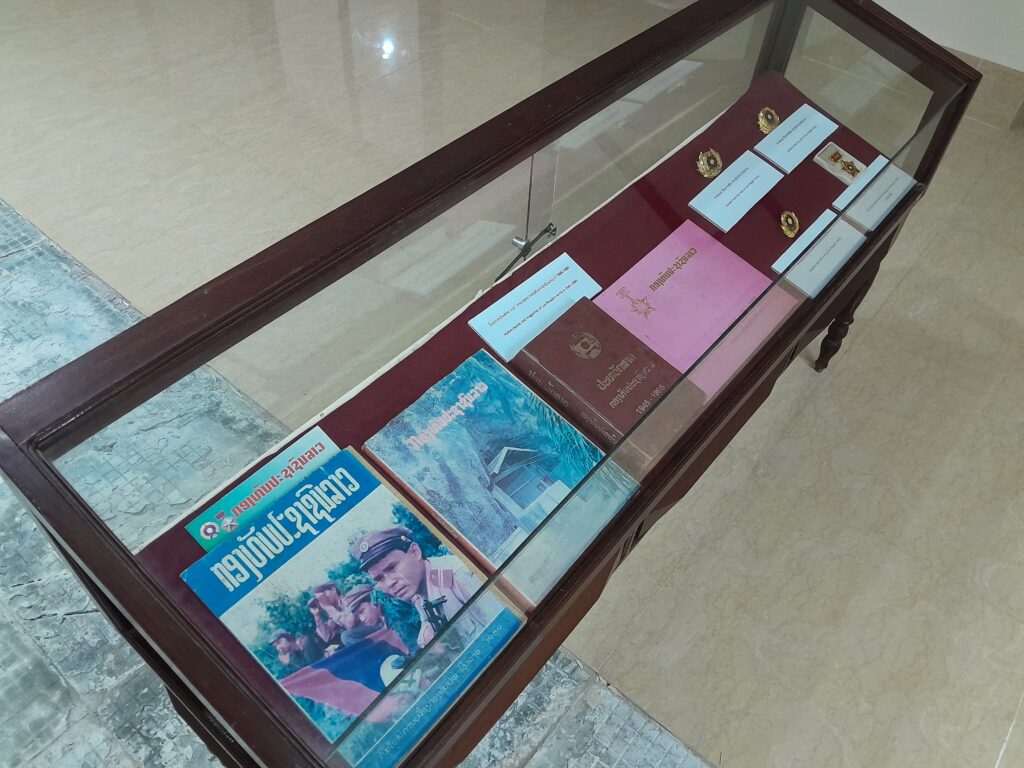

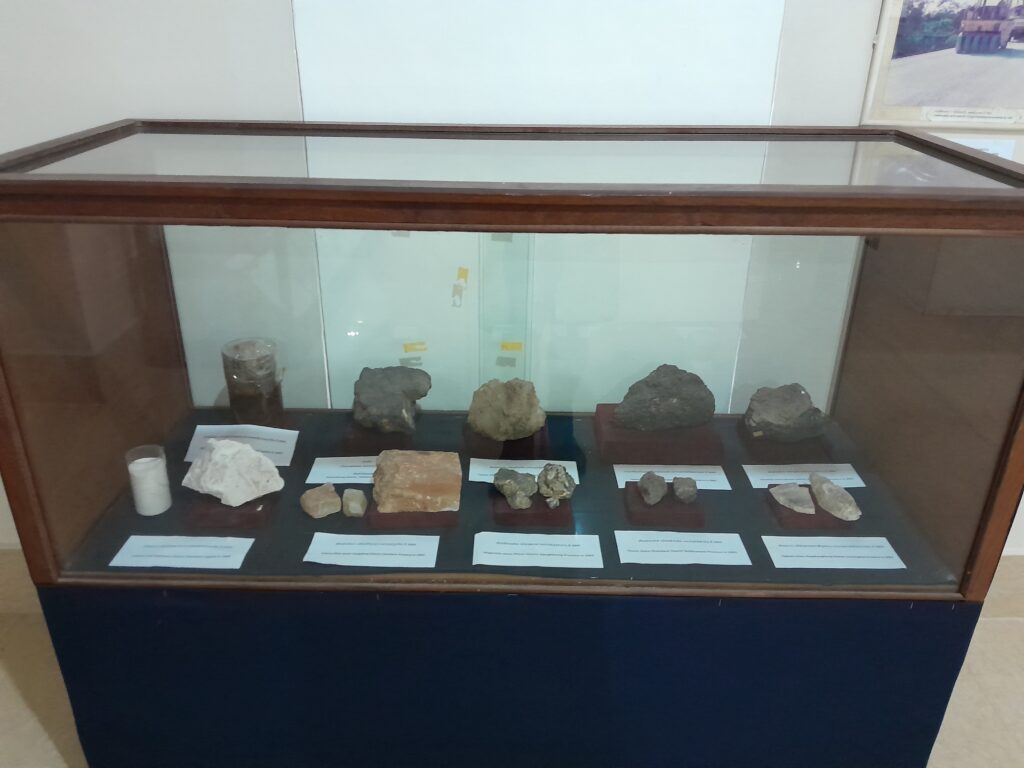

Inside, things are more relaxed. The museum was a little busier, though still far from crowded. Exhibits are divided into sections: Prehistory, Traditional Culture, The Laotian Civil War, and Modern History among them. The largest by far is the war section, filled with weapons, uniforms, and documentation from both sides of the conflict.

Some rooms feel sparse, with displays lining only the walls; others are densely packed with artefacts. It might give the impression that they don’t have much to show, but the reality is that what they do have is meaningful.

History, Unremembered

After spending time in both museums, I walked away with a stronger sense of Laos’ turbulent path to independence. The scars of war are still evident. Unexploded ordnance (UXOs), remnants of bombings that lasted nearly a decade, continue to maim and kill. Vast areas of land remain unusable, stalling the country’s development to this day.

The Laotian Civil War, often called the Secret War, is still largely unknown in the West. Even among those who’ve studied the Vietnam War or heard of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. “Secret” remains a painfully apt name. I might be inclined to call it the Forgotten War, but for something to be forgotten, it must first be remembered.

If you ever find yourself in Vientiane, take a detour out of the city. Spend a day in these museums. Witness the history of the country as they tell it themselves.

Remember. And don’t forget.