After spending some time in Vang Vieng, we took an eight-hour bus ride to Vientiane, the capital city of Laos. One of the first places we visited was near our homestay: the COPE Visitor Centre, where we would learn about Laos’ UXO crisis and the ongoing efforts to address it.

As it turns out, this would be the second time we followed in President Obama’s footsteps in Laos. Though this time, it wasn’t for a bowl of coconut milk, but for something far more sobering.

The COPE Visitor Centre1 exists to educate people about the lasting impact of UXO2 in Laos. I’ve written before about the country’s struggles with unexploded ordnance, but at the UXO Laos Visitor Centre, we’d found the doors closed. This time, we were able to step inside and see firsthand how UXO continues to affect daily life in Laos.

Laos holds the grim title of the most-bombed country in the world. During the Vietnam War, the U.S. waged a covert bombing campaign here in an effort to disrupt the Viet Cong’s supply routes along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. More than 270 million cluster munitions were dropped, and decades later, countless unexploded bombs still litter the countryside.

The COPE Visitor Centre is easy to miss. Tucked away within the grounds of the Centre for Medical Rehabilitation, it almost feels like walking into a hospital. But once inside, you’ll see their sign on a building to the right.

Just outside the COPE Visitor Centre, next to the Karma Cafe, stands a sculpture dedicated to the victims of UXO. It is built from 500kg of ordnance, including cluster bombs – some of the deadliest remnants of war. It’s a part of the continuing tradition of making art from materials originally intended to maim and kill.

Inside, another sculpture hangs from the ceiling, suspending deactivated bombies in midair. It visually demonstrates how a single cluster bomb scatters so many of these deadly submunitions across the land. It starts to sink in just how 270 million of these ended up being spread across the countryside.

This section contains a brief overview that gives the history and numbers of bombs dropped, as well as maps showing the most affected areas. The more densely populated towns and cities are generally safe, but the countryside remains riddled with these deadly remnants.

On this side there is also the Cave Cinema, which is modelled to look like an underground bunker used by the Pathet Lao in the revolutionary war. Here they screen documentaries about UXO in Laos. These movies are free to watch – one of COPE’s goals is to educate as many people as possible. Awareness is always the first step in solving anything.

While we were there, they happened to be screening a documentary about a team of bomb disposal experts. It showed how a team from New Zealand would go around villages, educating people about UXO, and risking their own lives to disarm or destroy any ordinance found. They know these bombs inside out – where they can be touched, how they can be moved, and whether they can be safely extracted or must be detonated on the spot.

One challenge they face is navigating local customs. Many villages have unique rituals that may seem unfamiliar to outsiders, but the team takes care to respect traditions while ensuring safety for all.

Another major challenge is that bomb materials can be valuable as scrap metal. Many locals will want to harvest the bomb for scrap metal, either unaware or not caring about the risk. This is why there is a major focus on education as well as disarmament. At least if people know the risks, they may think twice before trying to get at the scrap metal.

Part of their mission is to train Laotians how to do the job themselves, passing on the knowledge and enabling the country to help itself rather than depending on outside help. They have developed a system of training that teaches and empowers those who want to help. While the Kiwis led the team, most of its members were Laotian, from those moving the bombs to the leaders-in-training.

As the film ended, I sat in silence for a moment, thinking about the men and women risking their lives every day to undo a war that ended decades ago. For them, the war never truly stopped. After the credits rolled we left to the rest of the displays.

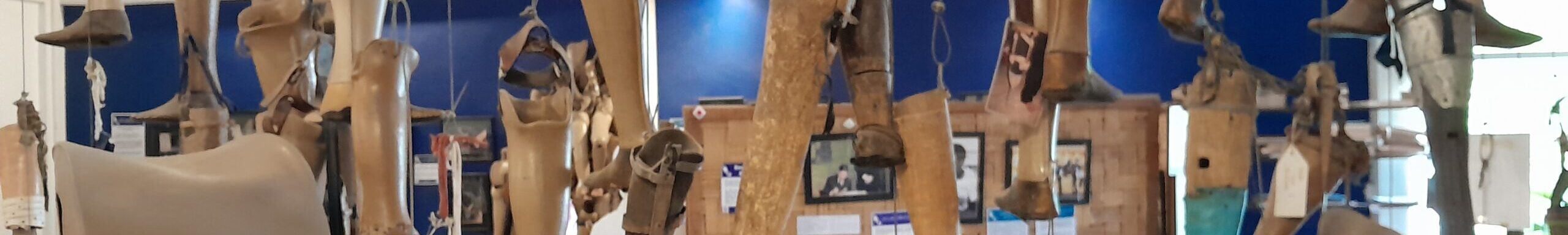

Half of the centre consists of a collection of used prosthetics, once provided to those who had been injured by UXO. This is COPE’s primary mission – they help to provide medical assistance to victims of UXO.

Here, we read story after story of people who had lost limbs and how COPE was helping them rebuild their lives. It’s but a glimpse into the number of victims around the country, and the efforts being made by COPE to support them.

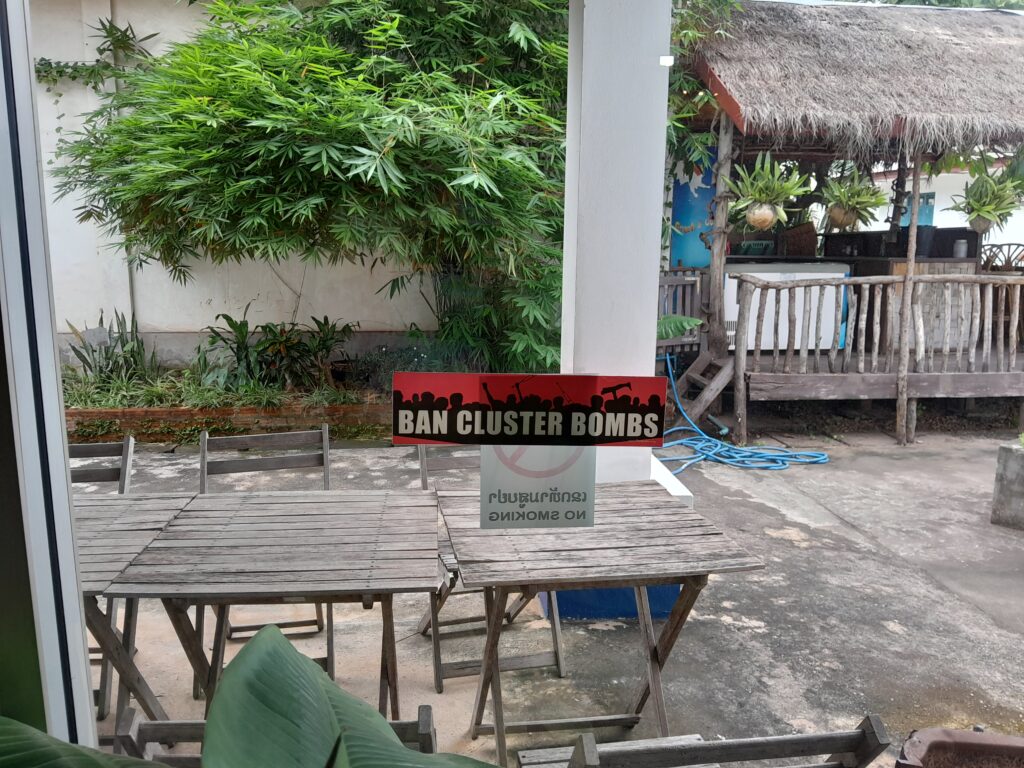

We leave, of course, through the gift shop. The profits here go toward COPE and toward helping the victims of UXO. On the way out we spotted a sign saying BAN CLUSTER BOMBS. Despite a global effort to get these bombs banned, the USA still uses them and even offered to send some to Ukraine to help in the war against Russia.

Seeing the devastation these bombs still cause in Laos five decades later, I can’t help but agree with the sign. These weapons don’t just end wars; they outlive them, claiming lives long after the soldiers have gone home. How many more generations have to suffer before we finally learn?

The people of Laos never chose this war. Yet half a century later, they are still the ones paying for it.